By EVOBYTE Your partner in bioinformatics

Introduction

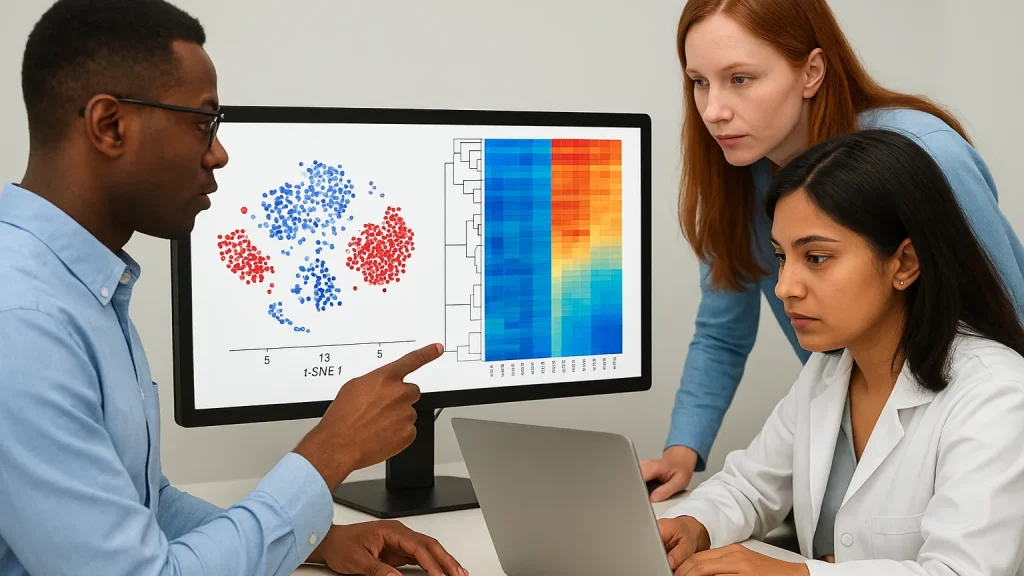

If you’ve ever stared at a single‑cell RNA‑seq (scRNA‑seq) UMAP from a tumor and wondered which clusters are truly malignant, you’re not alone. Malignant cells, in this context, are the transformed, genomically altered cells that drive the cancer. Telling them apart from the many normal cell types that inhabit the tumor microenvironment—fibroblasts, endothelial cells, macrophages, T cells—matters because everything downstream hinges on that split. Trajectory analyses, differential expression, ligand–receptor mapping, even drug target discovery will tell very different stories depending on whether you’re looking at tumor cells or the neighbors they’re persuading.

The catch is that scRNA‑seq gives us gene expression, not DNA. Expression alone can mislead when cell state, stress, hypoxia, or cell cycle masquerade as “tumor‑like” signatures. That’s why many pipelines lean on a reliable genomic clue embedded in transcriptomes: large‑scale copy number variation (CNV). By ordering genes along chromosomes and smoothing expression signals, we can recover broad chromosomal gains and losses that frequently accompany malignant transformation. Several tools operationalize this idea; in this post, we’ll focus on three widely used approaches—SCEVAN, inferCNV, and CopyKAT—and show how they help you call malignant cells when you only have RNA.

Why “malignant cell” calling is hard in scRNA‑seq

The problem starts with confounding. Many non‑malignant cell states elevate or depress large swaths of genes—think interferon responses or epithelial‑to‑mesenchymal transition—creating expression patterns that look tumor‑ish without any underlying genomic alteration. Conversely, some tumors, especially certain hematologic malignancies or early lesions, can appear nearly diploid at the chromosome scale, making their expression look surprisingly normal. On top of that, single‑cell data are sparse and noisy, so per‑gene variance is high and per‑cell coverage is low.

CNV inference approaches tackle these issues by collapsing gene‑level expression into chromosomal segments. Instead of asking whether a single oncogene is upregulated, they ask whether hundreds of contiguous genes on chr7 are consistently higher than baseline while chr10 is lower—exactly the kind of amplitude and breadth you expect from aneuploid gains and losses. When that pattern emerges robustly across a cluster of cells, it’s a strong signal of malignancy. Multiple benchmarking studies now show that CNV‑based classifiers can separate tumor from normal with good accuracy, while reminding us that reference selection, sequencing depth, and batch effects still shape outcomes.

How CNV‑based inference separates tumor from normal

Although implementations differ, most RNA‑to‑CNV pipelines follow a similar conceptual path. First, they define a baseline of “normal” expression—either using known non‑malignant cells in your dataset, external reference profiles, or cells marked by immune or stromal signatures. Next, they order genes by genomic position and compute a smoothed relative expression profile along each chromosome. Finally, they segment that profile into regions of putative gain, loss, or neutrality, often with a probabilistic model, and use the resulting aneuploidy pattern to classify cells as malignant or normal and to resolve subclones.

That classification is powerful because it aligns with tumor biology: malignant cells frequently carry broad aneuploid events that are rare among microenvironment cells. The trick is getting the baseline right. If your “normal” set contains many hidden tumor cells—or if your tumor is genuinely near‑diploid—the called CNVs will wobble. Modern tools try to mitigate this with more robust seeding of normal cells, joint segmentation across cells, and model‑based calling that tolerates noise.

Tool spotlight: SCEVAN, inferCNV, and CopyKAT

SCEVAN

SCEVAN (Single CEll Variational ANeuploidy analysis) frames CNV detection as a joint segmentation problem: it assumes cells from the same CNV clone share breakpoints, then performs a multichannel variational segmentation across cells. Practically, this boosts signal‑to‑noise by letting cells “vote” on shared events. Importantly, SCEVAN seeds high‑confidence non‑malignant cells using immune and stromal gene signatures, builds a relative expression matrix, then identifies malignant clusters and subclones. In evaluations across multiple tumor types, SCEVAN reported accurate tumor/normal discrimination and robust copy‑number profiles, including within immune‑infiltrated samples where references are messy. If your dataset mixes many microenvironment cells with a minority of tumor cells—and you don’t want to predefine normals—SCEVAN is a strong default.

inferCNV

inferCNV popularized the sliding‑window approach to visualize large‑scale CNVs from scRNA‑seq. It typically expects you to provide annotations that indicate which cells are normal, uses those to build a baseline, smooths expression along the genome, and segments gains and losses—often with a hidden Markov model (HMM)—to highlight aneuploid patterns. It remains widely used and well documented in Bioconductor, which makes it approachable for R‑first teams. Note, however, that the GitHub repository currently flags the project as “no longer supported,” and it points users to alternatives. In practice, many analysts still run inferCNV or its Python re‑implementation, infercnvpy, because they integrate cleanly with Seurat or Scanpy workflows and produce intuitive CNV heatmaps for tumor calling. If you use infercnvpy, keep in mind that some HMM features differ from the original R implementation.

CopyKAT

CopyKAT (Copy number Karyotyping of Aneuploid Tumors) takes an integrative Bayesian approach to estimate genome‑wide aneuploidy at roughly 5 Mb resolution from scRNA‑seq. A key feature is its data‑driven identification of diploid reference cells via mixture modeling, which helps when you don’t have explicit normal labels. In its foundational study, CopyKAT accurately distinguished malignant from normal cells across diverse tumors and resolved subclones with distinct expression programs. It also includes pragmatic conveniences like IGV‑ready segment outputs and mouse genome support, which can be handy in PDX or GEMM studies. If your dataset lacks clean labels for controls and you expect clear aneuploidy, CopyKAT offers a robust, turnkey path.

A quick R example with CopyKAT

You can go from raw UMI counts to malignant/normal calls in a few lines. This snippet assumes a genes‑by‑cells count matrix called exp.rawdata.

library(copykat)

ck <- copykat(

rawmat = exp.rawdata,

id.type = "S",

win.size = 25,

KS.cut = 0.1,

sam.name = "tumor01",

genome = "hg20",

n.cores = 4

)

pred <- as.data.frame(ck$prediction) # contains 'copykat.pred' = aneuploid/diploid

cna <- as.data.frame(ck$CNAmat) # segmented CNV matrix for plotting/integration

And a minimal Python example with infercnvpy

If you prefer Scanpy, infercnvpy plugs right in and computes CNV scores you can visualize on your UMAP.

import scanpy as sc

import infercnvpy as cnv

adata = sc.read_h5ad("tumor01.h5ad")

# 'cell_type' should include a category of known normals (e.g., T cells, macrophages)

cnv.tl.infercnv(adata, reference_key="cell_type", reference_cat=["T cell","B cell","macrophage"])

cnv.pl.chromosome_heatmap(adata, groupby="leiden", vmax=1.5, vmin=-1.5)

These examples gloss over quality control and normalization choices, which still matter. But they show how little code you need to surface aneuploid patterns that separate malignant from normal in practice.

Choosing, validating, and avoiding pitfalls

Start with your biology and your references. If you have a clean pool of non‑malignant cells in the same sample—immune and stromal populations often suffice—tools that expect explicit references, like inferCNV, are straightforward. If references are ambiguous or you anticipate strong infiltration, methods that jointly learn a baseline or segment across cells, such as SCEVAN or CopyKAT, are attractive. Importantly, recent benchmarking underlines just how sensitive performance can be to choices like sequencing depth, read length, and batch composition. When in doubt, try two tools and compare tumor calls on the same dataset; convergence boosts confidence, and disagreement tells you where to look closer.

Then validate like a skeptic. If you have matched DNA profiles—bulk WES/WGS, scDNA‑seq, or targeted panels—check whether the broad events line up. Even without DNA, you can sanity‑check that inferred aneuploid clones express epithelial markers in carcinomas or lineage markers in gliomas, and that immune and stromal compartments look diploid. Beware of diploid‑looking tumors; some malignancies truly lack large‑scale CNVs, so absence of aneuploidy is not proof of normality. In those cases, allele‑aware methods that integrate SNP information from RNA, like HoneyBADGER or CaSpER, can help by capturing copy‑neutral loss‑of‑heterozygosity or focal events invisible to expression‑only callers.

Finally, remember that “malignant” is not a monolith. CNV‑based calling is also a gateway to tumor phylogeny. Tools like SCEVAN and CopyKAT can resolve subclones that carry different chromosomal events, which often map to distinct cell‑state programs and drug sensitivities. That subclonal lens becomes especially useful when comparing primary and metastatic sites, pre‑ and post‑therapy samples, or spatially separated regions of the same tumor. In practice, analysts will often annotate malignant cells with both a coarse tumor/normal label and a finer subclone assignment, then use those labels to drive downstream DE, pathway, and interaction analyses.

Summary / Takeaways

When you only have scRNA‑seq, CNV inference is your best starting point for calling malignant cells. It replaces noisy gene‑level signals with chromosomal‑scale patterns that reflect core tumor biology, and it scales well to modern datasets. SCEVAN excels when references are messy and you want robust, joint segmentation. inferCNV remains a familiar, well‑documented baseline in R and has a growing Python ecosystem, though you should note its current maintenance status on GitHub. CopyKAT offers data‑driven reference discovery and practical outputs that make tumor/normal calling and subclone detection approachable in real projects.

No single tool is perfect. Reference selection, depth, and batch effects still shape results, as recent benchmarks emphasize. The most reliable path pairs a CNV caller with orthogonal checks—matched DNA when available, lineage markers, and biological plausibility. Start simple, validate assumptions, and use convergence across methods to back your calls. That way, the “malignant” label that anchors your entire analysis stands on genuinely solid ground. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Further Reading

- Delineating copy number and clonal substructure in human tumors from single‑cell transcriptomes (CopyKAT)

- A variational algorithm to detect the clonal copy number substructure of tumors from scRNA‑seq data (SCEVAN)

- inferCNV documentation (Bioconductor/GitHub)

- Benchmarking scRNA‑seq copy number variation callers

- HoneyBADGER: allele‑aware CNV and LOH from single‑cell RNA‑seq